NEW YORK – Outdoor tables saved thousands of New York restaurants from ruin when they were forced to close their dining rooms during the Covid-19 pandemic.

But four years after the start of an experiment that fundamentally changed the streetscape of New York and briefly gave the city a sidewalk café scene as vibrant as Paris or Buenos Aires, the carefree era of outdoor dining has come to an end.

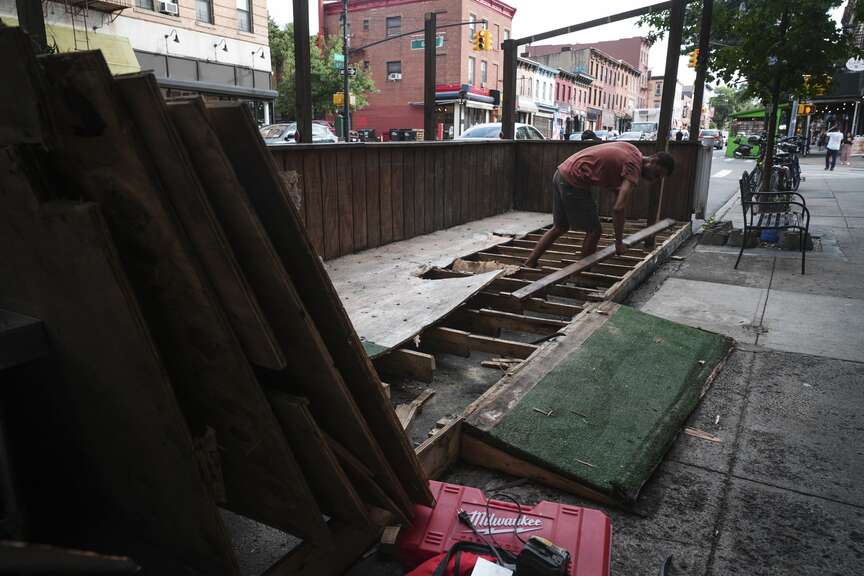

Over the weekend, restaurants faced a deadline to decide whether to comply with strict regulations for their outdoor dining options or dismantle them altogether. Thousands opted to tear down the plywood eateries that had sprung up like mushrooms in the early days of the pandemic.

Fewer than 3,000 restaurants have applied for street or sidewalk seating under the new system, a fraction of the 13,000 establishments that have participated in the temporary “Open Restaurants” program since 2020, according to city data.

Mayor Eric Adams said the new guidelines address complaints that the sheds have become magnets for rats and clutter, while also creating a straightforward application process that expands access to permanent outdoor dining spaces.

But many restaurant owners fear the rules will have the opposite effect: They would undo a legacy of the pandemic that gave them unusual freedom to convert parking spaces into rent-free extensions of their dining rooms with minimal red tape.

“They found a middle ground between doing one thing and saying another,” says Patrick Cournot, co-founder of the Ruffian wine bar in Manhattan. “They basically pushed us out.”

In the early days of the Covid pandemic, dilapidated plywood eateries seemed to spring up on the streets of New York almost overnight.

With its crowded sidewalks and busy streets, the city hasn’t been known for its outdoor dining. But after months of banning diners from gathering indoors, the city gave restaurants the green light to expand their dining areas to public sidewalks and streets.

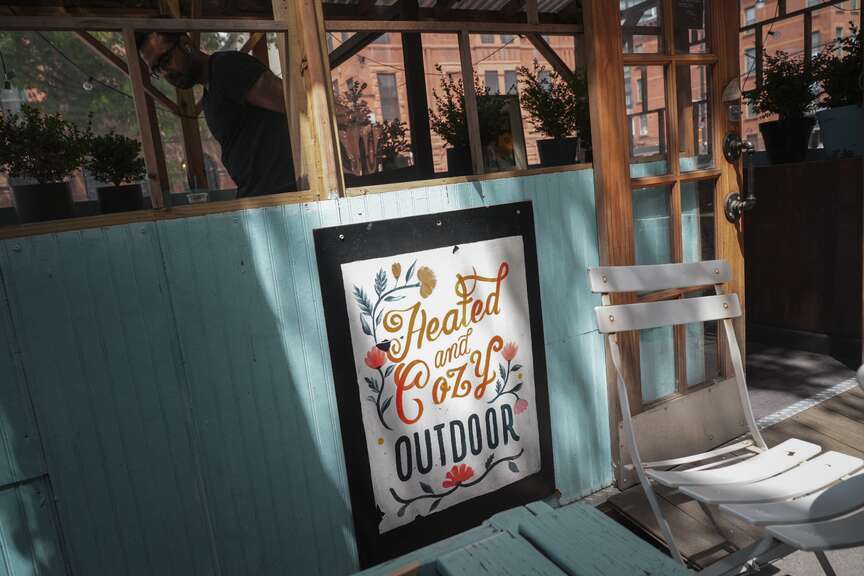

Simple sheds for outdoor seating were soon replaced or expanded with more elaborate structures that have remained standing long after the era of social distancing and sanitized grocery stores. Restaurants set up planters, twinkling lights, flowers and heating lamps so people could dine outdoors even in cold weather. More outdoor dining areas sprang up in heated igloos or with open fireplaces and under tiered roofs.

Today, these structures must meet uniform design standards and incur licensing and per-square-foot fees that can amount to several thousand dollars per year, depending on size and location.

However, the most significant change, according to many restaurants, is the requirement that street stalls be dismantled between December and April each year.

For Blend, a Latin-fusion restaurant in Queens that once won an Alfresco Award for its “exemplary” outdoor setting, that’s a deal-breaker.

“I understand they want to keep it in its original form and whatever, but it’s just too much work to have to take it down every winter,” said manager Nicholas Hyde. “We’re not architects. We’re restaurant managers.”

Blend’s 60 outdoor seats “kept us going during the pandemic” and have continued to be well used by patrons who “just want to have fun outside since Covid,” Hyde said. But after reviewing the application, they decided to remove the curbside structure and instead requested sidewalk seating that can remain year-round.

Of the 2,592 restaurants that applied for the new program, about half will forgo street seating and instead offer only sidewalk seating, according to the city.

Teacher Karen Jackson recently wanted to eat lunch indoors at the Gee Whiz Diner in Tribeca, one of the restaurants that removed their canopy sheds before the deadline.

Jackson said she had mixed feelings as she remembered that drinking coffee outdoors in a cabin was one of the few entertainment options available at the start of the pandemic.

“Some of them were really cute,” but others were unsightly and infested with rats, Jackson said.

“I think unfortunately the places with more money were able to build the nice sheds, while the places that were struggling were not able to,” she said.

Andrew Riggie, executive director of the NYC Hospitality Alliance, said the city should investigate why so few suitable restaurants applied and consider how expensive it would be to dismantle, store and rebuild the buildings each year.

Applications for street restaurants must also be considered by local councils, where some of the most heated debates about outdoor dining have taken place. Opponents have complained that the canopies take up parking spaces, contribute to excessive noise and attract vermin.

In the Lower East Side, a row of sheds with a sushi counter, a café, a Mexican restaurant and a Filipino restaurant stand next to each other.

Paola Martinez, a manager at Mexican restaurant Barrio Chino, acknowledged the trash problems and neighborhood conflicts — on one particularly busy night, an angry neighbor threw shards of glass at the building from an upstairs window, she said. But her restaurant has requested to remain on the street.

“It’s bringing a lot more people to the area,” she said. “It’s great for business.”

City officials say restaurants that missed the deadline are welcome to reapply in the future. Those who fail to do so will soon face a $1,000 fine for each day their establishments remain open.

As Cournot watched construction workers crowbar his once-vibrant edible bar, he described a sense of relief. He said the edible bars had become a symbol of an incredibly difficult time, when a colleague died of the virus and a drop in sales nearly ruined his East Village wine bar.

“When people say it’s the end of an era, I think it’s the end of a particularly terrible era for restaurants in New York,” Cournot said. “As with any prolonged group trauma, the positive things we feel collectively are a bit of a mirage.”

Workers demolish a dining room outside the Bricolage restaurant in the Brooklyn borough of New York on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

Workers demolish a dining room outside the Bricolage restaurant in the Brooklyn borough of New York on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo) A pedestrian stops on the sidewalk next to the outdoor dining area of Caffe de Martini in the Brooklyn borough of New York on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

A pedestrian stops on the sidewalk next to the outdoor dining area of Caffe de Martini in the Brooklyn borough of New York on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo) A customer takes a seat outside at Caffe de Martini in the Brooklyn borough of New York on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

A customer takes a seat outside at Caffe de Martini in the Brooklyn borough of New York on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo) A worker demolishes an outdoor dining hall in the Brooklyn borough of New York, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

A worker demolishes an outdoor dining hall in the Brooklyn borough of New York, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo) Owner Camila Soto stands outside Caffe de Martini, the cafe she runs with her husband in the New York City borough of Brooklyn, on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

Owner Camila Soto stands outside Caffe de Martini, the cafe she runs with her husband in the New York City borough of Brooklyn, on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo) Workers demolish a dining room outside the Bricolage restaurant in the Brooklyn borough of New York on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

Workers demolish a dining room outside the Bricolage restaurant in the Brooklyn borough of New York on Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo) Patrick Cournot, owner of Ruffian Wine Bar, stands in his outdoor dining room as it is demolished in New York on Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

Patrick Cournot, owner of Ruffian Wine Bar, stands in his outdoor dining room as it is demolished in New York on Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo) Workers demolish the outdoor dining room attached to the Ruffian Wine Bar in New York on Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

Workers demolish the outdoor dining room attached to the Ruffian Wine Bar in New York on Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)