The coalition government recently announced its plan to lift a ban on new oil and gas exploration to address the energy security challenge posed by rapidly dwindling natural gas reserves.

However, it is assumed – rather optimistically – that the lifting of the ban will encourage companies to invest in new gas fields.

In practice, these companies will carefully consider whether there is anyone at all to sell their gas to, or whether a future government might change the rules again.

Investors don’t like political volatility or market risk, and New Zealand is currently experiencing both.

The impending gas crisis

Model calculations by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) suggest that lifting the ban would result in additional emissions of 14 million tonnes of carbon dioxide by 2035.

This estimate is based on an assessment of the climate impacts resulting from the policy change compared to a baseline scenario.

The baseline commonly used for such assessments was set by the Climate Change Commission in 2022. However, the government argued that this value was already outdated and instead proposed another one that envisages 15% lower emissions from gases because the country is running out of gas supplies much faster than expected.

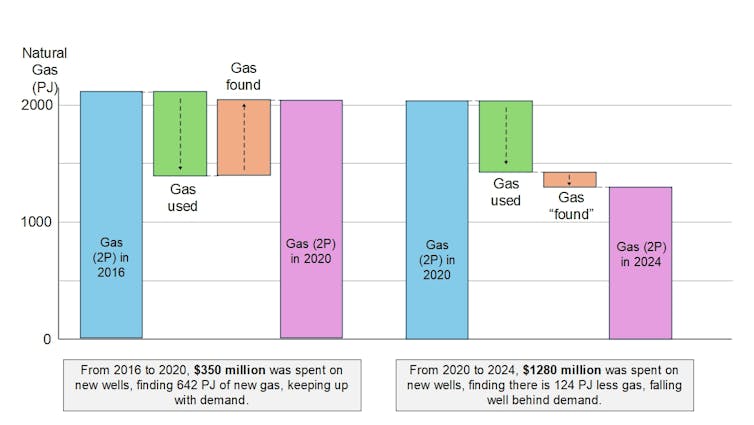

In some ways, New Zealand is slowly running out of gas. Energy companies are estimating how much gas is still underground and how long that resource will last. At the same time, they are drilling new production wells – worth $350 million between 2016 and 2020 – which is continuing to increase gas reserves and delaying the final end of gas reserves.

What has changed is that all the additional drilling in recent years has not produced much additional gas, despite record amounts being spent on new wells – nearly $1.3 billion between 2020 and 2024. Energy companies now believe there is less gas than previously thought.

It seems the end date is getting much closer, which is why the government has chosen a new baseline that reflects less gas (and lower emissions). This is a good outcome for the climate – but it may not be good for New Zealand’s economy in the short term.

Author provided the followingCC BY-SA

When the petrol runs out

As an island nation, New Zealand cannot easily import gas from abroad. There is no pipeline to Australia and building liquefied natural gas terminals is expensive.

We know from macroeconomics that when a resource becomes scarce in a closed market, the following things happen:

First, the amount of gas available to everyone needs to be prioritised, which means that some consumers may miss out. For example, the government is having difficulty renewing a contract to supply gas to schools, prisons and hospitals.

Second, the price of a resource increases when it becomes scarce. This is consistent with the experience of Pan Pac, a Hawkes Bay forestry owner and processor, who reported a tripling of gas costs, from $3 million a year to potentially $9 million at current prices.

Some would say the cure for high prices is just that: high prices. A gas crisis could ultimately shift demand to other sources such as domestic and industrial heat pumps, some of which were subsidised by the previous government’s Government Investment in Decarbonising Industry Fund.

But until that change happens, resource scarcity means that not as many goods can be produced, which could impact GDP. Methanex, a major exporter of methanol made from natural gas, is a key problem here. Less methanol would mean fewer exports and potentially job losses.

Methanex is already operating at reduced capacity and recently started Supreme Court proceedings against Nova Energy, which uses natural gas to generate electricity. Nova has stopped supplying gas to Methanex and the two companies are at odds over whether their contract allows this.

Difficult decisions lie ahead

It could take a decade or more to find, develop and bring a new gas field online. At the same time, according to MBIE forecasts, we can expect gas supplies to fall by half within six years if there are no new reserves (regardless of whether the government implements the lifting of the ban).

This means there may not be enough gas to simultaneously sustain synthetic (ammonia-based) fertilizer production, peak electricity generation, and methanol exports. What should take priority?

Ammonia is essential for agriculture and food production. In the future, we could replace the natural gas used to produce ammonia with green hydrogen produced from ultra-cheap solar energy. But this requires investment and determination.

Methanex exports $800 million annually, making it a major contributor to the economy. A transition to a green methanol industry is possible, but would require a huge amount of green hydrogen (produced with renewable energy) and green carbon dioxide (from biomass or direct air capture).

This would bring about a fundamental change in the economy, but would also require a lot of financial support.

Finally, we use a lot of gas in winter to keep the heat pumps running when the reservoirs’ water reserves are scarce. And at the beginning of the year we almost ran out of gas.

A future energy system with abundant solar power, grid-ready batteries and smarter use of hydropower could avoid this as gas supplies are phased out. The problem is that these solutions cost a lot of money and take time to implement. New Zealand doesn’t seem to have much of that.