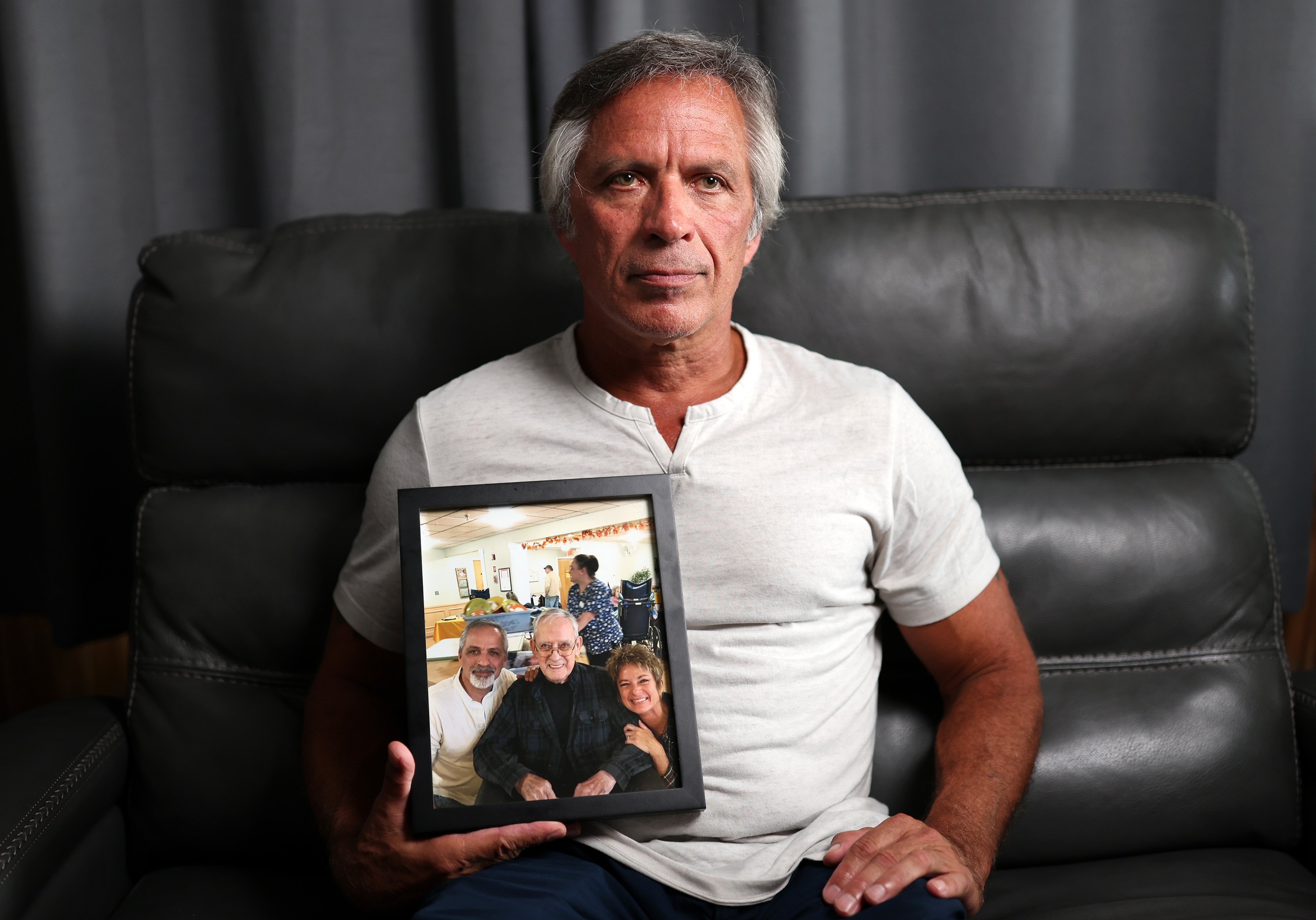

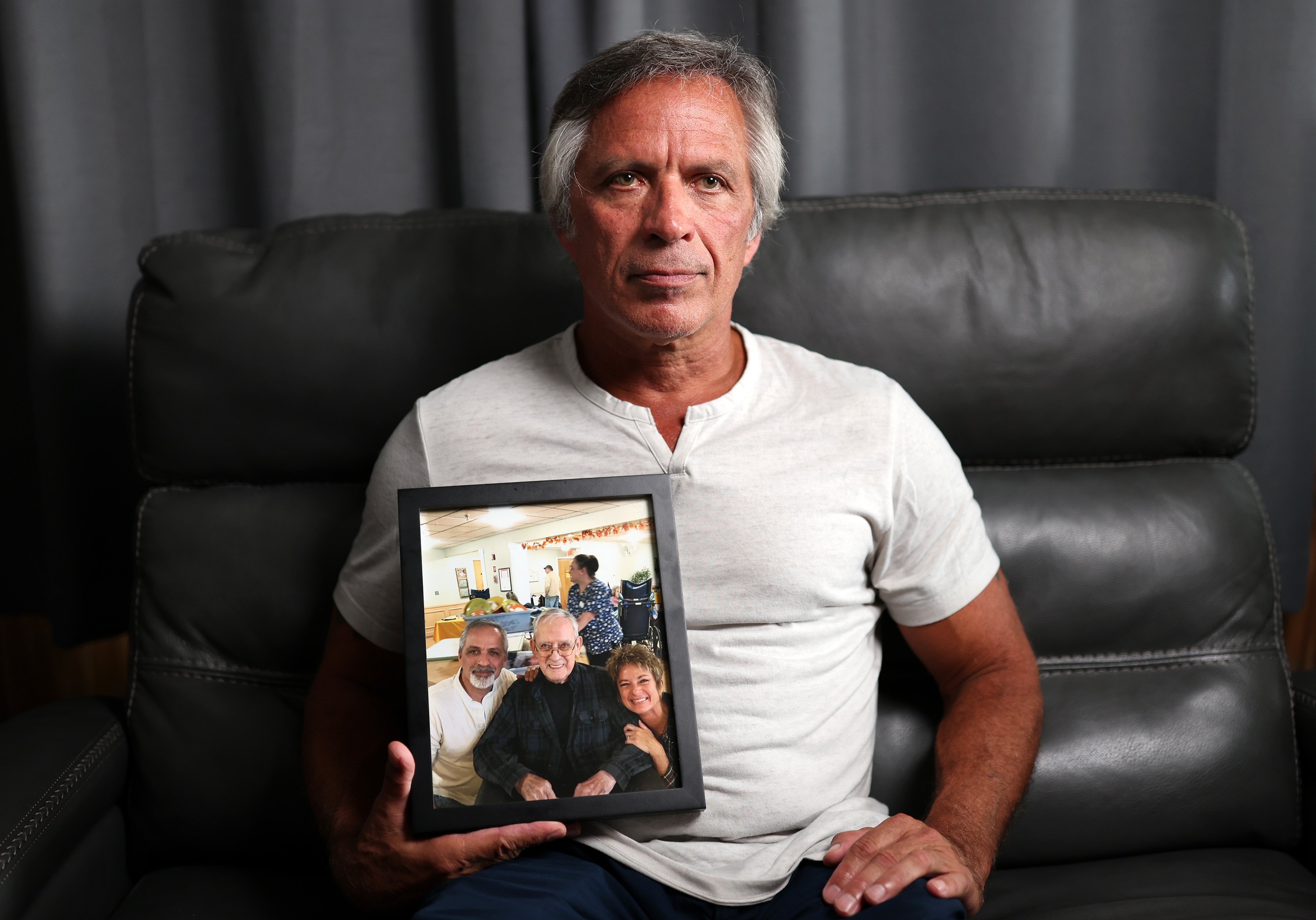

William Jipson Jr. with a portrait of himself (left), his father William Jipson Sr., and his sister Lynette Krapf. Jipson is one of several people who claim that Harold Lee Lamson Jr., a Lincoln funeral director, stole money from a loved one’s funeral fund. Jipson’s father died in 2022. Ben McCanna/Staff Photographer

Long before his death nearly two years ago, William Jipson Sr. had set aside thousands of dollars in a funeral fund to help ease the financial burden on his children of cremation and burial.

The value of the fund had grown to about $14,000 by the time of his death in December 2022 – more than enough to cover funeral expenses. But after the Lincoln-based funeral director he hired apparently kept all the money, Jipson’s son and daughter had to pay nearly $5,000 out of their own pocket for a headstone, “after we had already paid for it once,” said William Jipson Jr.

After months of delays and excuses, Jipson’s family has not seen a cent of their money.

“It’s all gone. He took it and spent it and that was it,” Jipson said. “It’s a terrible feeling knowing that someone wronged you and your father at the end of his life.”

The Jipson family is among a number of Mainers at the center of a criminal case against Harold Lee Lamson Jr., who runs four funeral homes in Penobscot and Washington counties. He is accused of embezzling thousands of dollars from their loved ones’ funeral funds between December 2022 and February of this year – adding undue expense and emotional distress to the painful process of grieving and arranging a funeral.

“It’s a slap in the face. Everyone wants to move on with their lives and deal with their losses,” Jipson said. “We went through 12 years of hell to take care of my father. … And then when he dies, you have to go through more years of hell.”

At one point, Lamson told Jipson’s sister he was waiting for the headstone to be finished being sanded and would send the money once he received the final invoice. But when she called the headstone company, they told her Lamson never placed the order and “this has happened a few times,” Jipson said.

Lamson is charged with four counts of theft by unauthorized transfer, a Class C felony. Each count is punishable by up to five years in prison and a $5,000 fine, and Lamson could be ordered to pay thousands of dollars in restitution.

He made his first appearance in Penobscot County Superior Court this month but was not required to enter a guilty plea. He will appear in court again in November.

He also faces the risk of losing his state funeral director license, and after years of complaints, he is currently suspended.

Lamson declined to answer questions about the charges by phone Thursday.

PROMISE AFTER PROMISE

Deborah Elms had hoped to bury her mother in Maine, where she had spent much of her life before moving to North Carolina in her final years to be closer to Elms.

Joyce Nicholson died there in January. Years earlier, she had founded a funeral home. But that company went bankrupt and transferred responsibility for the business to Lamson, Elms said.

“Although our family was not originally committed to (Harold) Lamson’s business, we appear to have become attached to him,” Elms wrote in a letter to police in February, less than a month after Nicholson’s death.

She said Lamson had no involvement with the funeral at all. But Elms still lost the nearly $4,000 her mother left behind because he failed to wire the money to the out-of-state funeral home that handled her mother’s funeral.

After at least eight phone calls over more than two weeks, Elms said she spoke to Lamson on Feb. 12. At that time, he promised to pay the North Carolina funeral home’s bill and send her the remaining balance of the trust.

The North Carolina funeral director also contacted Lamson demanding the money. Lamson responded a month after Nicholson’s death with an erroneous email apologizing for the delay and citing “more than 200 calls per year” as the reason for the slow response.

“While it was not my intention to wait this long, let alone 30 days, to pay this bill, time is passing too quickly,” he wrote in an email to the North Carolina funeral director, which Elms shared with the Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram. Lamson promised to send a check that same day, “no later than tomorrow.”

But he never did that, Elms said.

She ultimately paid the bill of about $3,100 with money she had set aside for a trip to Maine for the funeral of her mother and son, who had died a few months earlier, Elms said. Although she made it to Maine in June, the trip created an unplanned hole in her budget.

Elms said she suffered two stress-related heart attacks and had nightmares. She declined a telephone interview, fearing that telling the story would be too much for her.

“I am so upset when I think about him and the disrespect he showed me and the funeral home here in North Carolina,” Elms wrote in an email.

Hope for reparation

Both Jipson and Elms said they wanted reparations and Lamson in prison, but neither was convinced that any punishment could make up for the pain they felt he had caused.

Under Maine law, funeral homes are required to return any money left in certain types of funeral funds after funeral expenses are paid. If a funeral home is unable to provide any services, as was the case with Elms, it must return all proceeds from the fund.

There are three categories of burial funds in Maine: guaranteed service contracts, service contract loans, and existing life insurance contracts. Only the latter two contain provisions requiring the repayment of any remaining balance.

Although it is unclear how many Maine residents have established funeral homes because the state funeral directors association does not keep a census, such funeral homes are common throughout the state.

Rebekkah Martin, a former funeral home manager who worked in the industry for about 15 years, said it’s relatively rare to have money left over after funeral expenses, but federal and state laws set clear deadlines for when those funds must be deposited and repaid.

Jipson’s family should have been entitled to the nearly $9,000 left in the trust fund after the funeral, William Jipson Jr. said. But he is not optimistic about receiving a refund because he fears Lamson may file for bankruptcy to avoid paying.

Lamson attempted to file for Chapter 13 bankruptcy in March, around the same time the legal problems began to mount, but the case was dismissed in April because Lamson failed to provide all required documents or comply with his notice, according to federal court records.

According to his bankruptcy filing, Lamson owns several vehicles valued at more than $27,000, including a 2008 Cadillac and a 2018 Chrysler, as well as an investment property in Sedgwick valued at $80,000.

YEARS OF POTENTIAL ABUSE

Jipson said he could not understand why Lamson was given direct access to his father’s money without another layer of control, especially since Lamson had faced disciplinary action before.

“Shouldn’t there have been some safeguards in case someone misused the money?” said Jipson. “It seems a bit odd to me, but I don’t know the system.”

The complaints against Lamson go back decades.

In 2005, the state funeral director’s office suspended his license for six months after he pleaded guilty to attempted theft by insurance fraud, state records show.

The board suspended Lamson’s license in June after he violated an agreement, but until then he had operated funeral homes in Lincoln, Millinocket, East Millinocket and Danforth, according to his company’s website.

Maine residents can report possible misconduct by funeral homes to the Board of Funeral Services, said Joan Cohen, deputy commissioner of the Department of Professional and Financial Regulation, which oversees the board. But she said the board is not notified when transfers are requested or made unless someone files an official complaint.

Cohen said disciplinary action may depend on the specific arrangements with the funeral home, “but generally they include civil penalties, probation with conditions, suspension or revocation.”

She added that Lamson’s suspension was the only one the board has issued so far this year. Suspensions and revocations are relatively rare in Maine: The board issued none in 2023, only one revocation in 2022 and one suspension and one revocation in 2021, Cohen said.

Martin, the funeral home’s former director, said she had dealt with Lamson several times and faced excessive delays when trying to transfer trust assets for her clients.

“I wasn’t the least bit shocked when I heard this happened,” Martin said in a phone call Wednesday.

Martin said funeral funds are a valuable tool for consumers, but only as long as the funeral home is reputable. Prices can be locked in when the fund is established and the money can be more easily accessible than life insurance payouts, which can make the planning process easier.

“If you can’t admit your mistakes, you shouldn’t be in this business,” she said.

Copy the story link