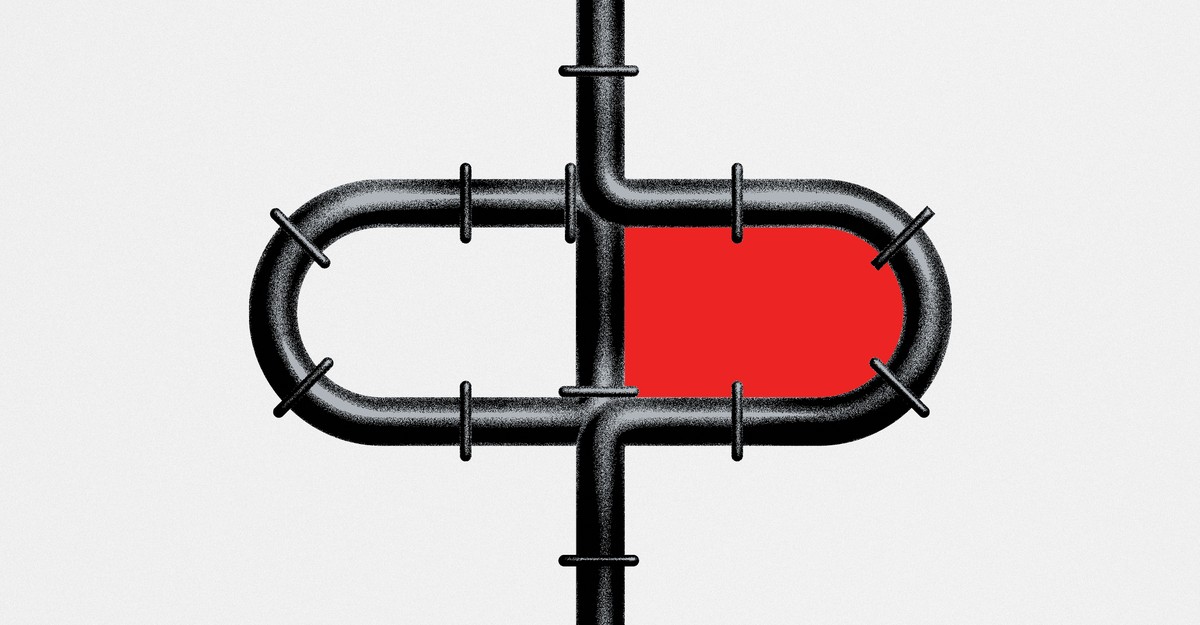

Not long ago, tracking the spread of a virus through wastewater samples was considered a novelty in the United States. Today, wastewater monitoring provides one of the most comprehensive pictures of the summer COVID-19 surge. This type of monitoring has been so effective at predicting the risks of the virus’s rise and fall that local governments are now looking for other ways to use it. That meant moving from tracking infections to tracking illicit and high-risk drug use.

Monitoring wastewater for viruses works because infected people shed tiny amounts of viruses; similarly, someone who has taken drugs clears biomarkers from their body. Because drugs tend to show up in wastewater before overdoses occur, city officials can detect when a potent amount of fentanyl, for example, is likely to be mixed with other drugs and alert residents. One city launched an aggressive campaign to dispose of prescription opioids after discovering the drugs in large quantities in its wastewater. Other communities have used wastewater monitoring to distribute Narcan and study the effectiveness of programs funded by opioid settlements.

Wastewater monitoring for drug use has been routine in Europe and Australia for at least a decade, but it is also spreading rapidly in the United States. Biobot Analytics, a biotechnology company that was one of the CDC’s key labs for monitoring COVID wastewater, is now receiving federal funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and is working with 70 sites in 43 states to monitor wastewater for illicit drugs. Other commercial and academic organizations are pursuing similar initiatives.

More than 100,000 Americans die of overdoses each year. More precise data from wastewater monitoring could help health departments target more specific interventions. But to get such specific data, samples must be taken closer to the source and from smaller populations—small enough that police could theoretically use this information to target specific communities and neighborhoods. This monitoring isn’t limited to communities, either: Prisons and office buildings have also contracted with Biobot to track illegal drug use. If wastewater monitoring is detailed enough, many researchers and health officials worry that law enforcement could use it against the people it’s meant to help.

For governments, monitoring drug use through wastewater is fairly easy. For example, Marin County in Northern California expanded its pandemic-era wastewater program last year to combat drug overdoses, now the leading cause of death for residents under 55. Samples from wastewater treatment plants are sent to Biobot, which uses mass spectrometry to determine which drugs are prevalent in the community. Using that information, Marin has developed an early warning system for overdoses and detected xylazine (or tranquilizers) in the area for the first time through its wastewater. While traditional monitoring relies on emergency records and autopsy reports, this method allows authorities to avoid some of those dire consequences, Haylea Hannah, a senior analyst at the Marin Health Department, told me. (The county can’t yet say whether wastewater monitoring has directly reduced overdoses.) More than 100,000 people contribute to each collection area: Marin intentionally keeps sample sizes large so there are fewer collection points and lower costs — and to avoid ethical concerns.

For Biobot, such a program fits the company’s aspiration to “do policy and health care in new ways,” Biobot CEO and co-founder Mariana Matus told me. In her view, wastewater monitoring could also inform health authorities about sexually transmitted infections, tobacco use and even our diets. When I asked her what it was like to generate such data without people’s consent and concerns about its use, she told me she viewed those concerns as “academic” concerns that have nothing to do with “what happens in reality.” For now, Matus is right: Collection sites are currently so large that the information can’t be traced back to an individual or household. And from a legal perspective, there are precedents for wastewater being considered garbage—once it’s on the street, anyone can take it. But, some experts ask, what if wastewater were more like cellphone location data that follows us everywhere and over which we have far less control? Although everyone can decide for themselves where and how to dispose of sensitive waste, using the public sewer system is unavoidable for most people in the USA.

As samples get smaller and wastewater data becomes more detailed, health officials will inevitably have to grapple with the question of “how detailed is too detailed,” Tara Sabo-Attwood, a professor at the University of Florida who researches wastewater monitoring for drugs, told me. The experts I spoke with agreed that block-by-block sampling runs the risk of failing to accurately identify specific households; most seem comfortable with a catchment size of at least several thousand. That question should be addressed before a city or company collects data so specific that it violates people’s privacy or is used for law enforcement, Lance Gable, a professor of public health law at Wayne State University, told me.

Simply collecting and sharing this data can have consequences beyond their intended public health purposes. Some governments are as open about drug data as they are about virus data: Tempe, Arizona, which tracked opioids through wastewater even before the pandemic, posts the data on a public online map showing weekly opioid use in its eight collection areas. Recently, the state of New Mexico monitored illicit and prescription drug use at its public high schools through wastewater and publicly posted the results for each school. These dashboards provide data transparency and do not reflect a level of information that could be used to identify individuals. Still, police departments could use the data to increase their presence in certain neighborhoods, potentially triggering a self-reinforcing cycle of increased police presence and drug detection. Substance use patterns could affect property values; teachers could avoid working at certain schools.

To Neelke Doorn, a professor of hydraulic engineering ethics at TU Delft in the Netherlands, these potential impacts are starting to look like function creep—when the technology loses its original purpose and begins to serve new, potentially troubling purposes. The lines between public health and law enforcement data have been broken before: Gable pointed out that hospitals have, for example, forwarded pregnant mothers’ positive drug tests to police. And in wastewater monitoring, the line between public health and law enforcement is already blurring—both the National Institutes of Health and the Justice Department have funded this research. If wastewater monitoring for drugs evolves into a more detailed examination of, say, a neighborhood block, that data could justify searches and arrests, undermining its original intent. After all, criminalizing drug abuse has been shown not to improve drug problems. And Sabo-Attwood warns that wastewater monitoring, like much of public health, relies on trust, and that trust evaporates when people fear their data could be misused for other purposes.

Monitoring wastewater for drugs in buildings only exacerbates these problems because data at that level could more easily identify individuals. While such monitoring is not yet widespread, it is already growing. In the U.S., a private company can currently test a building’s wastewater for illegal drugs without informing its employees or residents, Gable told me. Early in the pandemic, some college campuses monitored individual dorms for the virus through wastewater analysis—an approach that could help detect illegal drug use.

Supposedly, collecting data via wastewater could be less biased and intrusive than other methods of drug testing. But Doorn cautions that this is only true if samples are taken across all neighborhoods, or at least randomly, rather than testing only selected communities. In prisons, however, where drug testing is already routine, studies suggest that wastewater analysis could actually be a less invasive and more accurate alternative to individual urine tests – and help ensure that law enforcement takes a public health approach to combating drug use.

Marin County has tried to navigate this ethics scandal by actively soliciting the views of drug users. Initially, only 13 percent of participants in the county’s focus groups opposed wastewater monitoring, while the rest – 44 percent – were in favor or neutral. Unsurprisingly, the biggest concern was the possibility that the data could be used for other purposes, particularly by police. But if the county’s strategy can maintain public trust, a potentially controversial monitoring method could bring great benefits to the people it is intended to help.