While solar power is growing extremely fast in absolute terms, the use of natural gas to generate electricity continues to outpace renewables. But that is set to change in 2024, as the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) has analyzed the numbers for the first half of the year and found that wind, solar and battery power plants were each installed at a pace that dwarfs new natural gas generators. And the gap is set to widen dramatically by the end of the year.

Solar and battery boom

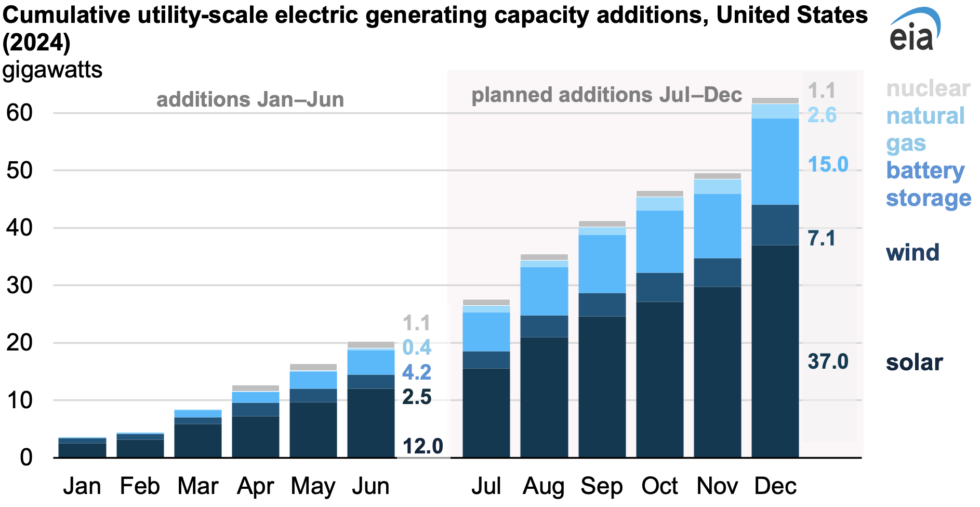

According to EIA figures, about 20 GW of new capacity was added in the first half of this year, and 60 percent of that was solar. Over a third of the new solar installations occurred in just two states, Texas and Florida. Two projects with a capacity of over 600 MW came online, one in Texas and the other in Nevada.

Next come batteries: The U.S. installed 4.2 gigawatts of additional battery capacity during this period, representing over 20 percent of total new capacity. (Batteries are treated by the EIA as an equal source of electricity generation because they can add power to the grid when needed, even if not continuously.) Texas and California alone accounted for over 60 percent of these gains; if Arizona and Nevada are included, the total is 93 percent of installed capacity.

The clear pattern here is that batteries will be deployed where there is solar, so that electricity generated during peak daytime demand can be used to meet demand after sunset. This will help existing solar plants avoid curtailing electricity production during the off-demand periods of spring and fall. This, in turn, will improve the economic case for installing additional solar plants in states where production already regularly exceeds demand.

Wind power, on the other hand, is moving more slowly, with only 2.5 GW of new capacity added in the first six months of 2024. And for perhaps the last time this decade, additional nuclear power was brought online, with the fourth 1.1 GW reactor (and the second recently built) at the Vogtle site in Georgia. The only other gains came from natural gas-fired plants, but these amounted to just 400 MW, or just 2 percent of total new capacity.

The EIA has forecast through the end of 2024 based on capacity additions in the works, and the overall state of things is not changing much. However, the pace of installation is picking up as developers rush to get their project online within the current fiscal year. The EIA expects just over 60 GW of new capacity to be installed by the end of the year, with 37 GW of that coming from solar. Battery growth is continuing at a rapid pace, with 15 GW expected, about a quarter of the total capacity additions for the year.

Wind power will account for 7.1 GW of the new capacity, natural gas 2.6 GW. If the contribution of nuclear energy is added, 96 percent of the capacity additions in 2024 are expected to be CO2-free. Even if battery expansions are ignored, the share of CO2-emitting capacity remains extremely low at just 6 percent.

Gradual changes in the network

Obviously, these numbers represent peak production from these sources. Over a year, solar in the U.S. produces about 25 percent of its rated capacity and wind about 35 percent. The former number is likely to decline over time as solar becomes cheap enough to make economic sense in places that don’t get as much sunshine. In contrast, wind’s capacity factor could increase as more offshore wind farms are completed. Many of the newer natural gas plants are designed to operate intermittently so they can provide power when renewables are underproducing.

A clearer picture of what is happening is to look at the sources of electricity generation that are being retired. In the US, 5.1 GW of capacity went offline in the first half of 2024, and aside from 0.2 GW of “other” capacity, all of that came from fossil fuels, including 2.1 GW of coal capacity and 2.7 GW of natural gas. The latter includes a large 1.4 GW natural gas plant in Massachusetts.

Yet total shutdowns this year are expected to be just 7.5 GWO—less than in the first half of 2023. That’s likely because U.S. electricity use rose 5 percent in the first half of 2025, according to EIA figures released Friday (note that this link will take you to more recent data in a month). It’s unclear how much of that is due to weather—much of the country experienced heat, likely increasing the need for air conditioning—and how much is due to rising consumption in data centers and the electrification of transportation and household appliances.

This data release provides details on where the United States got its electricity from in the first half of 2024. The changes are not dramatic compared to last month. Nevertheless, the changes last month are good news for renewable energy. In May, wind and solar energy production increased by 8.4 percent compared to the same period last year. In June, it was even more than 12 percent more.

Given EIA’s expectations for the rest of the year, the key question will be whether the pace of new solar installations will be sufficient to offset the decline in production that will occur in the U.S. as we move into the winter months.