Meteorologists warned in the spring that the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season could be particularly dangerous, as the combination of warm sea surface temperatures and a looming La Niña climate pattern would favor the formation of tropical storms. But while the season’s typical peak occurs in early September, the basin is eerily quiet. The most recent named storm, Ernesto, dissipated around August 21. So were the dire hurricane predictions wrong? Where are all the storms?

In short, the answers are “no” and “it’s complicated.”

According to experts, this season has already been strong despite the current lull – and could become even more active. So far this year, there have been five named storms in the Atlantic: two tropical storms, two hurricanes and one major hurricane. The severe hurricane Beryl reached Category 5 earlier than any previous storm in the Atlantic. “We have definitely started with an extremely active season,” says Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami.

To support science journalism

If you like this article, you can support our award-winning journalism by Subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you help ensure the future of influential stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world today.

And considering the number and strength of individual storms is just one way to evaluate a hurricane season. Another important tool for understanding tropical activity is a measurement called accumulated cyclone energy (ACE), which represents the total activity of tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic. To calculate ACE, scientists count the wind speeds of all storms strong enough to have a name—those with peak winds of at least 39 mph (62 kph)—every six hours. Each storm’s wind speed is squared, and then the values are added together. This is done four times a day throughout the season.

This year’s ACE value is still 50 percent higher than the season-to-date average from 1991 to 2020, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – not a quiet year. According to McNoldy, much of the power of the season so far was due to Hurricane Beryl, which was both strong and long-lasting. Ernesto also contributed significantly to the current ACE value.

In addition, the Atlantic hurricane season lasts until November 30th, so there is still plenty of time for activity to pick up again and undo the calm of the last few weeks. “Just because we don’t know anything about the last few weeks and maybe this week, it’s definitely too early to say anything about the entire hurricane season,” says McNoldy.

But scientists are actually “pretty baffled” by the current situation. The same factors that worried them before this hurricane season are still at play, McNoldy says. Sea surface temperatures in the eastern Atlantic, Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico are all nearly two degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) above average, providing plenty of warm water for tropical storms to feed on. And as predicted, the El Niño climate pattern that normally suppresses hurricanes in the Atlantic has shifted toward La Niña conditions, which feature lower wind shear rates that help tropical storms break apart.

So the stage is set for severe storms to form in the Atlantic – they just don’t seem to. The trends are too preliminary to make more than hypotheses, but to understand the situation, scientists are turning their eyes to Africa, where the seeds of severe weather that form hurricanes are formed. Here, two phenomena may be playing a role in the current hurricane lull.

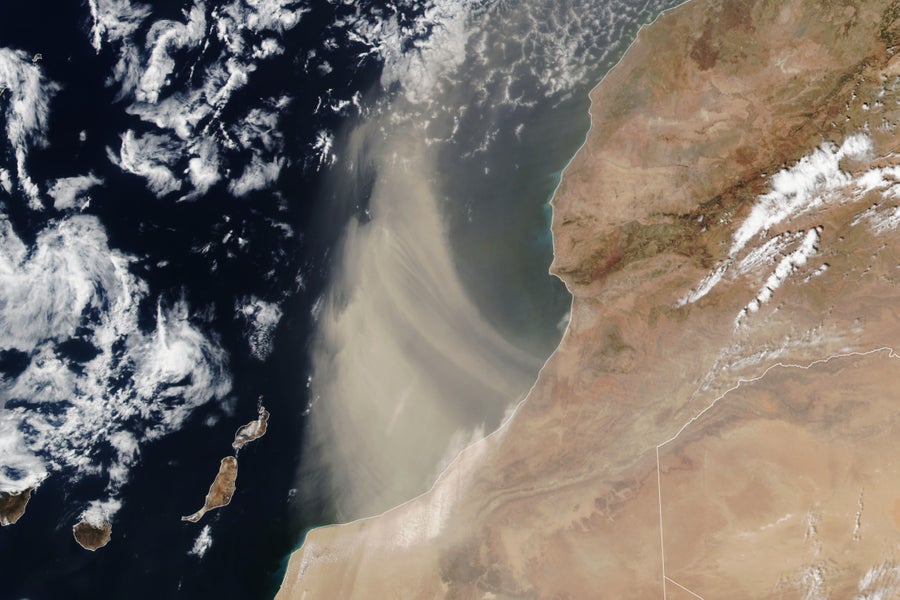

On August 24, 2024, thick bands of Saharan dust streamed across the Atlantic from the southern coast of Morocco.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Lauren Dauphin, using VIIRS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE, GIBS/Worldview, and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership

One is the cloud of dust that rises over the Sahara Desert and is carried by winds across the Atlantic. It makes sense that this dust could affect hurricanes because it travels along a similar path to approaching tropical storms – and because dust is dry and storms feed on moisture. And some research has shown interactions between Saharan dust and tropical storms, although the relationship is quite complicated, says Yuan Wang, an atmospheric scientist at Stanford University and co-author of one such study published earlier this year.

That work showed that Saharan dust can reduce the amount of rainfall a hurricane brings. But Wang suspects it could also reduce hurricane formation. “I think it’s very possible that the dust plays a role in this year’s drought-hurricane season,” he says, although that explanation remains speculative. “I think we still need to do very thorough scientific research to be able to do an attribution analysis.”

A second interesting factor is that the West African monsoon has been unusually wet this year, says Kelly Núñez Ocasio, an atmospheric scientist at Texas A&M University. The West African monsoon is a seasonal wind pattern that brings rain from the Atlantic to West Africa between June and September. Núñez Ocasio has studied how the monsoon affects hurricane formation. And in a paper published earlier this year, she and her colleagues modeled how the atmosphere responds to additional moisture.

These simulations suggest that when conditions are wetter, the West African monsoon pushes a band of air called the African easterly wind northward. Under normal conditions, this wind flow creates atmospheric disturbances called African easterly waves that can develop into hurricanes once they reach the Atlantic. But when the wind flow is in a more northerly position, it appears to inhibit the development and survival of these waves, Núñez Ocasio and her colleagues found, making hurricanes less likely despite the moisture.

She says these conditions in Africa could continue to dampen this year’s Atlantic hurricane season. “I don’t think things are going to change so dramatically that we’re going to suddenly see a rapid cluster of hurricanes before October,” says Núñez Ocasio. “The situation is just too stable, and when conditions are stable, it’s hard to make them unstable. That will take some time.”

Núñez Ocasio wants meteorologists to look beyond the Atlantic to assess conditions for hurricane formation, but she adds that it is still important for the general public to remain vigilant in the Caribbean and the southern and eastern United States, as even unnamed storm systems could cause severe flooding and other damage.

Meteorologists agree. “We continue to be concerned about development risks across the entire Atlantic basin, because it only takes one tropical storm or hurricane to trigger a potential disaster,” says Dan Harnos, a meteorologist at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

Meteorologists also warn that despite the current calm in the Atlantic, severe storms could still occur this season. “Conditions still seem very favorable for above-average activity during the rest of the hurricane season,” says Jamie Rhome, deputy director of NOAA’s National Hurricane Center. And late-season storms can be brutal: late October 2012, for example, spawned Hurricane Sandy, which hit parts of the Caribbean before racing toward the east coast of the United States and devastating New Jersey and New York.

Fluctuations in hurricane activity are not unusual, McNoldy stresses. “You can have weeks of good hurricanes and then weeks of bad hurricanes, and that’s pretty normal,” he says. He points to 2022, when there were no named storms in the Atlantic between July 2 and September 1 – two full months of eerie silence. But in September, both Fiona and Ian developed into major hurricanes, with the latter causing severe flooding in Florida and along the North Carolina coast.

“I think it’s too early to write this season off,” McNoldy said. “Even if we have this long quiet period, we still have a long hurricane season ahead of us.”