In some ways, Britain has been one of the most successful countries in the world in tackling climate change over the past few decades. But that progress could be undone and wiped out for a few years with a little cheaper gas for a few people and a lot of profit for even fewer people.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation narrated by Noa here.

The reason is that the new Prime Minister, Liz Truss, has promised to lift a 2019 ban on “fracking” to extract shale gas in England. It is true that the transition to low-carbon energy was never going to be easy. But shale gas is methane, a fossil fuel with high carbon emissions, while fracking has already been tried unsuccessfully in the UK and its resumption is not based on new evidence that could significantly change the results. This is not an act based on data, but on desperation and dogma.

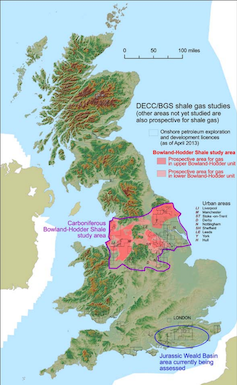

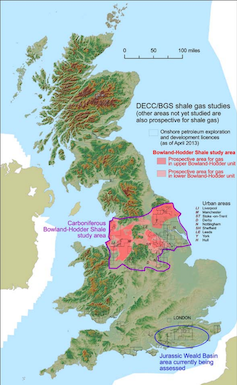

The first problem is that there simply isn’t enough gas. For fracking to become a viable large-scale business in the UK, very large geological deposits of shale gas are essential. The enthusiasm for shale gas trials in the UK between 2011 and 2019 was based on government-commissioned reports from the British Geological Survey (BGS), which predicted that there could be many decades’ worth of gas reserves beneath central and northern England, south-east England and central Scotland.

However, such reports are expressly speculative and always calculate the maximum possible resource. Usually, after more detailed work, commercially viable reserves do not exceed 10% of the original estimate.

In the UK, the results of the test drilling were mostly poor. The drilling triggered several small and several medium-sized earthquakes. And what made matters worse: rock samples were analyzed and it turned out that they contained only small amounts of recoverable gas or oil.

The gas and oil present are not under the same extreme pressure as in the more successful shale fields of the US and Canada. These high pressures are a sign that there is plenty of easily recoverable fuel.

The assumption that Britain had a similarly large shale gas potential assumed that its shales had not already produced gas – that the potential was not there yet. But laboratory results show that gas has already been produced in these rocks in the geological past. Over millions of years, Britain’s landmass has been buried, uplifted, buried again and eroded. This complex geological history has provided many opportunities for gas to escape through the land’s many faults and cracks, leaving only the remnants. If Britain wants to build a major fracking industry along the lines of the US, it is 280 million years too late.

Read more: How we discovered that UK shale gas reserves are at least 80% smaller than thought

Skepticism and mistrust widespread

Even if enough gas is found, the major challenge remains to obtain specialized equipment and skilled workers for drilling and development. To supply the country with gas in large quantities will require thousands of wells over a period of ten years. Disposing of huge amounts of saline and radioactive wastewater is another major challenge.

It is no wonder, then, that the British government is reluctant to claim that local consent is required before fracking can begin. Given that fracking has a difficult history in the UK and has always been imposed top-down by the David Cameron government, there is widespread scepticism and distrust in the communities affected by the planned drilling.

These doubts can perhaps be turned into acceptance through longer dialogue, better information and trust-building – but that takes years. Another option proposed by some shale gas developers would be to make direct cash payments to residents and communities – in some cases as much as 6% of initial revenues. The US shows that sharing the financial spoils can enable a rapid change of mind. But strong regulations are needed to prevent shale gas developers from paying a community money to support development, then quickly leaving an area once the gas is exhausted, leaving the consequences to languish. A fracking well drilled near Preston in 2019 is still not capped.

Britain actually had large deposits of shale oil and gas on land a long time ago. But because the country has the wrong geological history, that oil and gas have long since disappeared, draining away along the numerous faults and fractures. American and Canadian geology is much simpler, and that is why shale gas is still there.

Solar and wind power generate cheaper electricity than gas, and methane leaks cause measurable warming of the Earth. Both the International Energy Agency and the IPCC are clear that fossil fuel production must be rapidly scaled back. Why should the UK risk its best international reputation and future world leadership in the clean energy industry? Fracking in the UK presents numerous commercial and technical challenges that may or may not be overcome. There is a huge public perception that needs to be changed, and the environmentally acceptable path forward is very unclear.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Stuart Haszeldine receives research funding from the UK research councils EPSRC and NERC and SGN Scottish Gas Networks. He receives funding for hydrogen research from Horizon Europe and EPSRC. He is a member of the BEIS CCUS Council and advises NECCUS on a voluntary basis on coordinating CCS developments in Scotland.