A Roman prison described as a “lawless place” has been identified thanks to a collection of disturbing ancient graffiti, a study reported.

The site, located at the archaeological site of Corinth in Greece, appears to have been used as a prison during late antiquity, according to an article published in Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies in Athens.

Corinth was an ancient city-state that became one of the largest and most important Greek settlements of antiquity. The city was captured and almost completely destroyed by Roman troops in 146 BC and remained largely abandoned for over a century. It was not until 44 BC that the city began to recover, when the Roman general and politician Julius Caesar restored the city as a provincial capital.

P. Dellotas/Courtesy of Corinth Excavations

Corinth underwent a series of renovations in the late 4th and early 5th centuries, and the buildings that served as a prison were among those affected by the works. The buildings appear to have been repurposed and renovated in the late 4th century, when the site was converted into a prison, the study found.

The structures continued to be used to imprison people for at least a few centuries, if not longer, said lead study author Matthew Larsen of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark. Newsweek.

Documented evidence of such a prison site from antiquity is significant given the rarity of such finds.

“I have been working with several colleagues for eight years on the history and archaeology of prisons in the ancient Mediterranean. The archaeological remains of prisons have proven extremely elusive and difficult to identify with certainty,” said Larsen.

The ancient prison is located on the site of the Roman Forum of Corinth, in the heart of the city. In Roman cities, the forum was a multi-purpose public square or open area, usually located in a central location. It served as a meeting place and a kind of marketplace. But it also had other purposes, as it was the scene of political debates and other activities.

Larsen was able to identify the ancient prison in a part of the Forum known as “Boudroumi and the Northwest Shops.”

“Boudroumi is a Turkish loanword for ‘dungeon’ and was used by the people of Corinth in 1901 to describe the building, of which only the top of the domed roof was visible,” Larsen said. “The northwest shops are a series of 15 rooms opening onto the forum, with the boudroumi being the central room. It is slightly larger than the other 14 rooms.”

In the first centuries of their use, the rooms were probably used for commercial purposes. After an earthquake at the end of the 4th century, they were completely rebuilt and converted into a prison, according to the researcher.

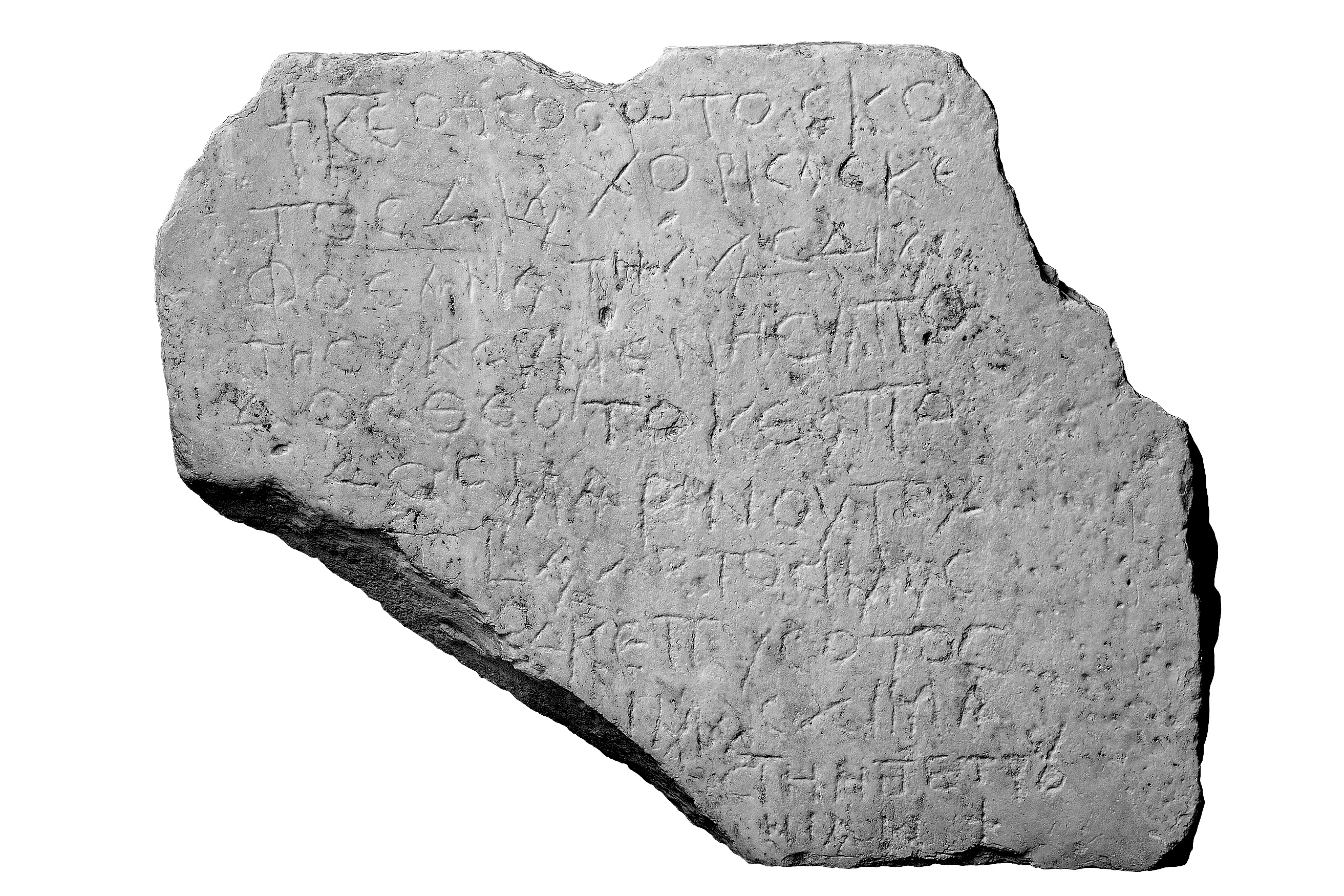

Larsen was able to identify these buildings as prisons largely based on the graffiti he found on the floor tiles in the area.

Photograph by J. Herbst and M. Letteney; Model by M. Letteney/Courtesy of Corinth Excavations

“When I heard about this graffiti, I immediately thought: If we can prove exactly where these floor tiles were found, and if they are in situ – not floating or deposited there, but in situ as flooring – then we can confidently identify the site as a prison,” he said.

“We know from the 1901 excavation reports that the floor tiles were in their original, renovated position when they formed the floor of the boudroumi and the northwest shops. We also know that they were moved and reused from another location, as they were broken on one or more sides.”

The graffiti appears to have been written into the tiles by prisoners. Some contain phrases in which prisoners beg for their release, while others demand “no mercy” for the people who imprisoned them.

The graffiti that Larsen highlights include the following phrases:

- “May the fate of those who suffer in this lawless place benefit them. Lord, show no mercy to the one who cast us here.”

- “Lord, let them die a horrible death.”

There are also graffiti wishing luck to beautiful women who love unmarried prisoners, several game boards and a picture that looks like a soldier. There was also a lot of graffiti on the walls, although hardly any of it has survived today.

The graffiti was written by prisoners, taking into account the broken edges of the floor tiles. This suggests that the inscriptions can be dated to the period when the site was used as a prison.

Reconstruction by Niels Bargfeldt/Supported by the Carlsberg Foundation

“When I set out to identify prison remains, I knew it was going to be difficult, and I joked, ‘Prisons aren’t the kind of place you can identify just by an inscription’ – but this is almost as clear evidence, which surprised me,” Larsen said.

Larsen is currently leading a research project to develop a classification system for Roman prisons and is working with his colleague Mark Letteney on a monograph on imprisonment in the ancient Mediterranean.

“We are part of a growing wave of historians who show that while prison is often portrayed as a modern invention, our research holds a mirror up to the present and confronts us with a longer, more complicated history than some have previously acknowledged,” Larsen said.

Do you have a tip for a science story that Newsweek should cover? Have a question about archaeology? Let us know at [email protected].

References

Larsen, MDC (2024). A prison in late antique Corinth. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, 93(2), 337-379. https://doi.org/10.2972/hes.2024.a929939