Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

The presidential debate took place tonight as wildfires rage in Nevada, Southern California, Oregon and Idaho. Louisiana is bracing for a possible hurricane. After a year of flooding and storms across the country, more than 10 percent of Americans are left without home insurance as the insurance industry abandons vulnerable areas due to climate change. Record heat waves have strained infrastructure and killed hundreds of Americans. For millions more, the devastating effects of climate change are already on their doorstep.

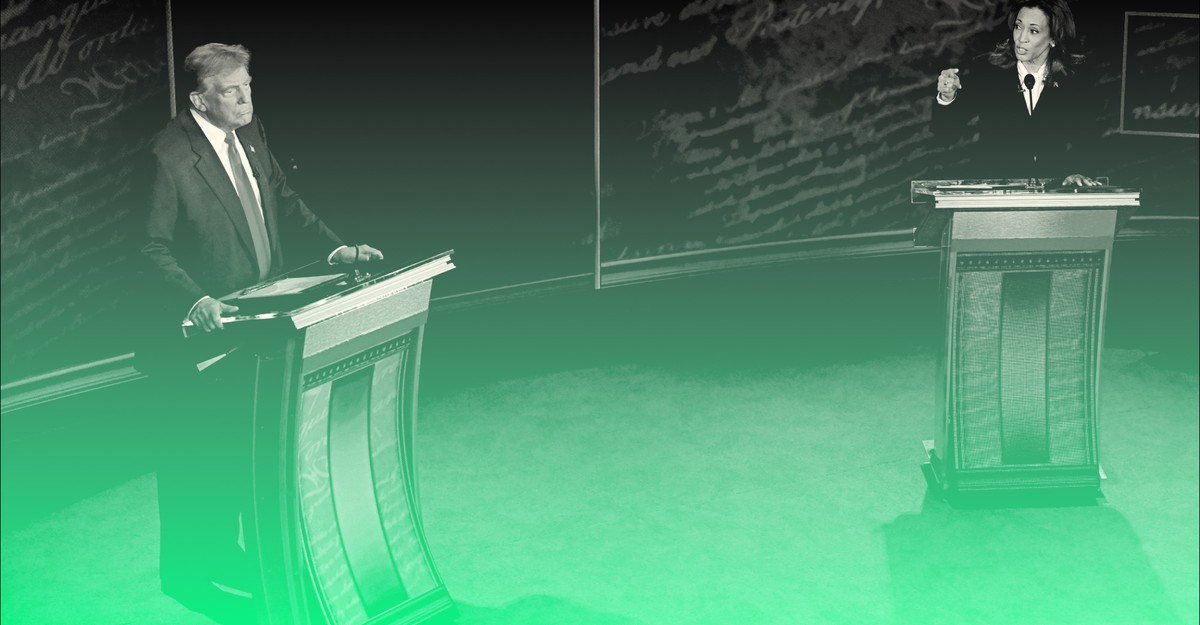

These are all material hardships—tragedies, health risks and inconveniences—that America’s two presidential candidates could use to appeal to voters. One could argue that voters deserve a plan that addresses these problems. Yet during the debate, the climate discussion didn’t go much beyond Donald Trump’s isolated mention of solar power—he warned that under a Kamala Harris presidency, the country would “go back to windmills and solar power, where they need a whole desert to get energy,” before adding, incongruously, “I’m a big fan of solar power, by the way.” Harris, meanwhile, reiterated her statement that she would not ban fracking. The moderators broached the subject, asking the two candidates, “What would you do to combat climate change?” Harris briefly mentioned that people are losing their homes and insurance premiums are rising due to extreme weather. And she stressed that “we can handle this problem” – before talking about American manufacturing and U.S. gas production, which have reached historic highs. Trump talked about tariffs on cars made in Mexico. Neither mentioned what they would do to deal with the threat of more chaotic weather.

Yet the near absence of climate talk in the 2024 presidential election has nothing to do with the reality the next president will face. Harris, if she is serious about continuing Joe Biden’s legacy, will eventually have to articulate a plan for moving forward that goes beyond implementing Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the largest climate policy the country has ever seen. And Trump may not be worried about rising carbon dioxide emissions, but he will have to grapple with the reality of climate change, whether he likes it or not. The next president will be a president of climate catastrophe, likely forced by circumstances to answer at least one question about climate change. And at that point, the question is not just, “What would you do to combat climate change?” but, “How will you help Americans deal with its impacts?”

Right now, the political discussion about climate change in America is effectively on ice. Trump has promised at several rallies to “drill, baby, drill,” and he told oil executives it would be a “deal” if they gave $1 billion to his campaign, given the money he would save them by rolling back taxes and environmental regulations. Harris, on the other hand, would almost certainly take a stance on climate change at least as strong as Biden’s, but her campaign team at least seems to have decided that it is not politically advantageous to raise these issues at live events. She has barely mentioned climate change, although she has generally affirmed in her platform that she will work for environmental justice, protect public lands, and expand the IRA.

And yet this year alone, the United States has experienced 20 disasters that caused over a billion dollars in damage. That’s part of a general uptick in such high-destructive events. (In the 1980s, there were fewer than four such events per year on average.) How the federal government plans to help communities affected by storms, floods and fires should be a staple of any debate today. Beyond disasters, one might also ask the candidates about their plans for dealing with heat: Under the Biden administration, for example, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration has taken steps for the first time to address the problem of workers dying in extreme heat. But the climate hazards facing all Americans go far beyond that and will worsen over the next four years. What do the candidates have planned for them? What will happen to the ailing National Flood Insurance Program? How will firefighters, now routinely stretched beyond their capacity, be supported? Climate chaos is an oncoming train, but there are levers to slow it down and mitigate its impact. Harris’ official platform says she will increase “climate disaster resilience.” Neither Trump’s nor the Republicans’ platform mention the issue at all.

Whether the two candidates would try to slow climate change themselves is another question. Trump’s position is clear: He has pulled the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement before and would likely do so again to block climate action on the international stage. Project 2025, a policy paper closely associated with the Trump campaign, calls for the dissolution of the federal departments of climate research and weather forecasting, along with a long list of environmental policies and the mechanisms to enforce them.

Harris’ intentions are also clear: she will address climate change, although the details are unclear. The US recently became the world’s largest oil and gas producer and currently produces more oil than any other country at any time. The country is essentially already Drill, baby, drill. This represents a clear contradiction to U.S. climate policy. What, if anything, would a Harris presidency do about it? She has already backtracked on her 2019 campaign promise to ban fracking and said she would not do so if elected president. (This remark came after Trump attacked her stance in Pennsylvania, a key fracking state, and is one of her most forceful statements yet on all things climate.) She reiterated this position during the debate, speaking of the country’s success as an oil producer and stressing the importance of relying on “diverse energy sources so that we reduce dependence on foreign oil.”

Harris can certainly tout the Biden administration’s record of passing the IRA and quietly releasing updates on energy infrastructure policy, such as a recent update on solar permitting reform. But the IRA alone is not enough to meet the U.S.’s emissions reduction goals or its energy supply needs. Harris will surely something to further shorten the moment in climate policy, she should be elected president. But we don’t know what. Trump, meanwhile, would be a major setback for America’s climate future.

At least for some viewers watching tonight’s debate in frigid Louisiana, burning Iowa or sweltering Arizona, these questions are likely to be the main issues. Even if the climate crisis is not the most important issue for most voters, it can still influence elections, according to a voter analysis of the 2020 presidential election. And more than a third of U.S. voters say climate is very important to them in this election. But it’s not just about how people will vote in November. It’s about how the next president will address what comes to the country with greater urgency every year.