In the past, it has been written in /Film (by me) that Star Trek excels in avoiding the boring cliches of action thrillers, favoring instead philosophy, diplomacy, crisis, teamwork, and character. Action movies require heroes to use violence to solve their problems, and most films in this genre end with a brawl, a shootout, or a chase. Often, the hero even goes so far as to murder the villain. Action movies use feigned violence as a simple solution to complex problems. How simple would it be if you could fix the world’s ills by pushing a man off a cliff!

Star Trek has always been, at least in my opinion, an important counterpoint to action-forward thinking. Yes, many Star Trek stories (especially the 13 films) end with an explosion and/or the murder of the villain, but the series has always stayed truer to its principles when solving its problems with diplomacy and heroism.

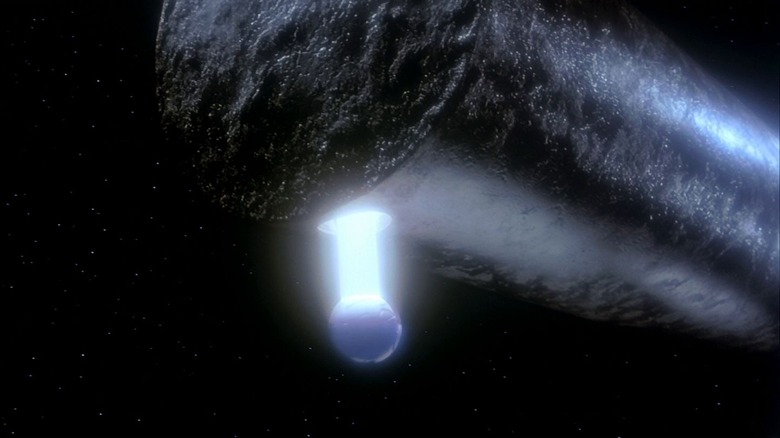

Case in point: Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. This film was the highest-grossing Star Trek film from 1986 to 2009 and features no villains, no action sequences, no shootouts, no fist fights, and no chases. For those unfamiliar, the story is about a mysterious probe that unexpectedly begins to explore Earth’s oceans in search of humpback whales, hunted to extinction many years earlier. The crew of the Enterprise travel back in time to 1986 in a converted Klingon ship to rescue a pair of whales and bring them back to the 23rd century to divert the probe.

According to the 1995 book “The Art of Star Trek” by Judith and Garfield Reeves-Stevens, director Leonard Nimoy pursued a clear anti-action policy for “Voyage Home” and explicitly banned six action concepts from his script.

The six anti-action mandates

In the book, Nimoy said that he wanted to leave out the following in his film:

“No dying, no fighting, no shooting, no photon torpedoes, no phaser explosions, no stereotypical villain. I wanted people to really have fun watching this movie (and) if we presented them with some big ideas somewhere in the mix, that would be even better.”

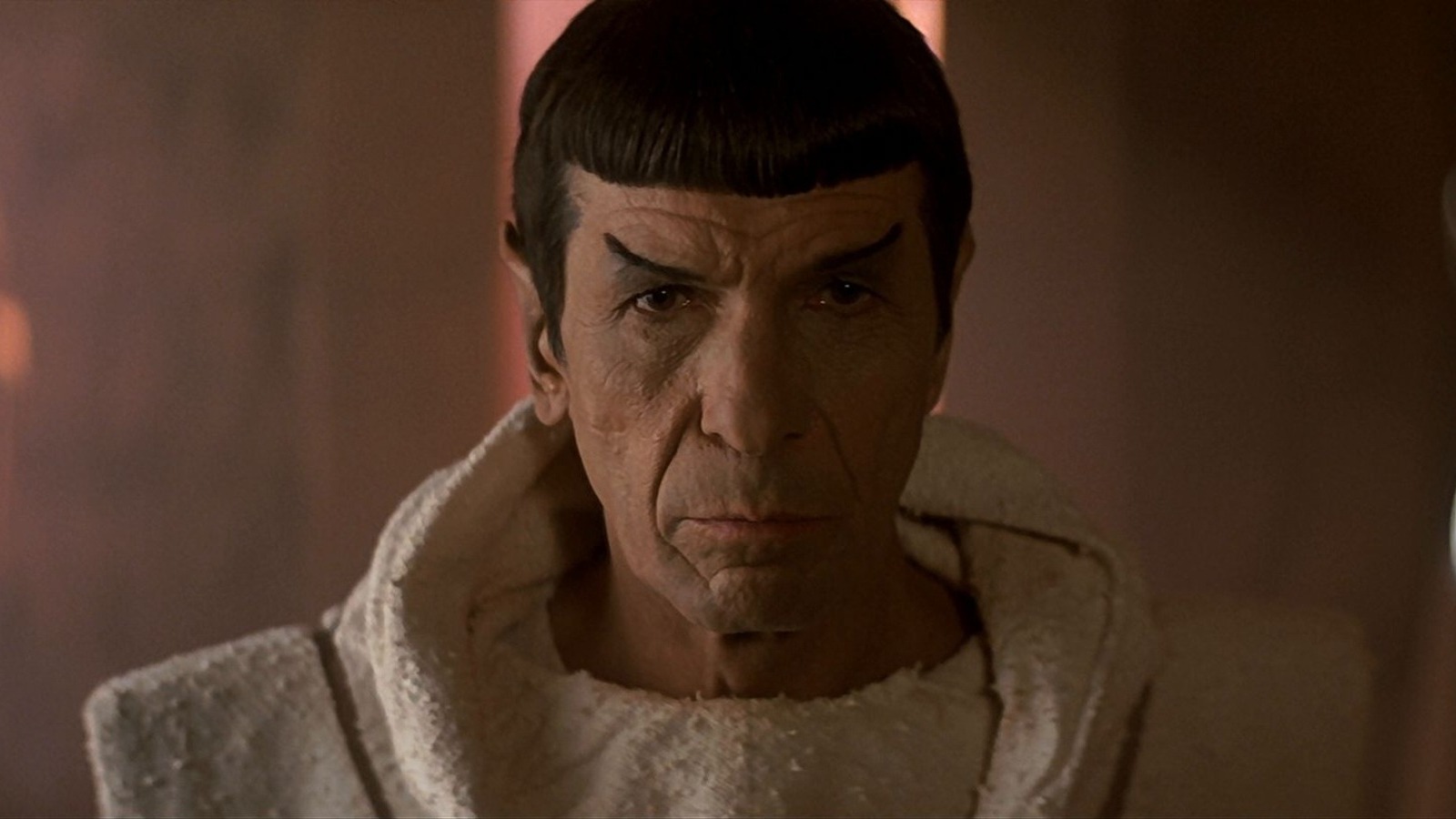

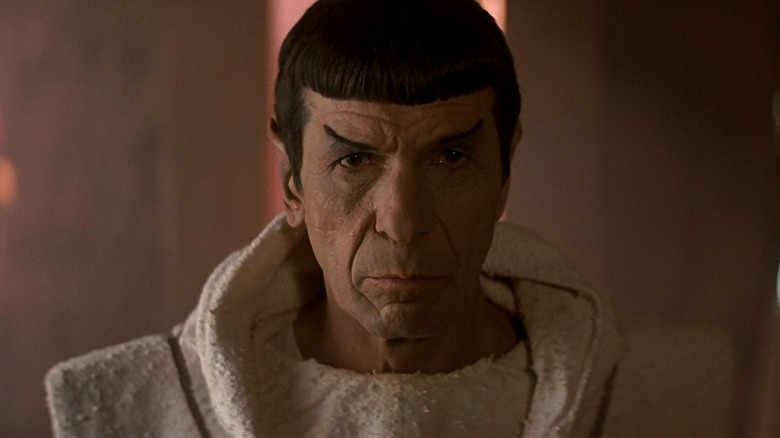

This was perhaps a reaction to the previous two Star Trek films, which were full of death and violence. Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan featured a stereotypical villain, lots of phaser shots, lots of gunplay, lots of photon torpedoes, and numerous deaths, including the death of Spock (Nimoy). At least there wasn’t much hand-to-hand combat. Star Trek III: The Search for Spock was about the Enterprise crew hijacking the Enterprise to reunite Spock’s disembodied consciousness with a newly grown version of his body. However, in the process, Kirk’s son died, the Enterprise exploded, and the crew went into hiding, knowing they would be court-martialed.

Star Trek IV, Nimoy said, was the perfect time to keep the story light. A time-travel story about ecology and biodiversity was just what the doctor ordered, and audiences responded enthusiastically; the film grossed $133 million at the box office against a $26 million budget. As mentioned, it was the most lucrative Trek film until JJ Abrams made his reboot in 2009. Perhaps ironically, Abrams’ film was the most action-packed Trek film up to that point, violating all the guidelines set by Nimoy’s Voyage Home.

What is the big idea?

And of course, Star Trek IV was not a grim race against time, but a quirky fish-out-of-water comedy that brought laughter to the 23rd century Enterprise crew as they deal with Reagan’s America. In one scene, Spock confronts a punk rocker. In another, Kirk (William Shatner) has to sell his personal belongings to get money, something no one has in the 23rd century. The lightness only benefited the film.

As for a big idea, Nimoy cleverly turned his film into an environmental rant, arguing that hunting a species to extinction is illogical and will have unknown, horrific consequences for the future. If we don’t save the planet’s animals now, we could be condemning ourselves to an alien death hundreds of years from now. In early brainstorming sessions, Nimoy figured the endangered animal in question should be a small, ugly fish called a snailfish. As the story progressed, the animal in question became a whale, which offered more tantalizing storytelling possibilities; how do you transport a pair of whales onto a spaceship, for example? And how do you get parts for a Klingon ship in 1986 (since the ship needed repairs, of course)?

So Nimoy got all six of his mandates, came up with some well thought-out ideas and produced the most successful Star Trek film.

It’s odd, then, that so many of the recent Star Trek films were based on The Wrath of Khan. Four Star Trek films in a row have revolved around villains seeking revenge, and each one has ended in a brutal, deadly battle. If a 14th Star Trek film is ever made, perhaps it will also be a light-hearted time-travel adventure about ecology.